Tagged: “Future”

World Education Week Features Dr. Enright’s Forgiveness Education Initiatives

World Education Week 2021, an annual celebration of practical educational innovations that kicks off this week, will focus on Dr. Robert Enright’s Forgiveness Education initiatives—particularly those in Greece, Northern Ireland, and Liberia (West Africa).

The event, sponsored by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, provides a platform for schools and education organizations to share how they have developed their expertise with the express purpose of inspiring other schools and organizations to understand the journey to excellence. More than 100 schools and organizations around the world will be sharing their unique expertise and success stories with a global audience.

“The best thing we can do to build a better future is empower our students with the social and emotional tools they will need to live healthy, productive, thriving lives,” according to Andrew Serazin, President of Templeton World Charity Foundation. “Forgiveness is one of those critical tools.”

“The best thing we can do to build a better future is empower our students with the social and emotional tools they will need to live healthy, productive, thriving lives,” according to Andrew Serazin, President of Templeton World Charity Foundation. “Forgiveness is one of those critical tools.”

As outlined on the World Education Week website, Forgiveness Forum, a panel of experienced forgiveness teachers and educational advocates from around the world will share their unique experiences building forgiveness into curriculums and discuss its impact on classroom dynamics, on student attainment outcomes, and on teacher well-being.

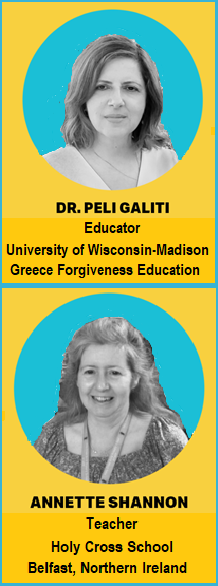

Two members of that three-person panel of experts have a combined 20 years of experience either teaching students or educating teachers about Dr. Enright’s Forgiveness Education Program:

- Dr. Peli Galiti,

Ph.D., M.Ed., has been conducting training workshops for Greek teachers for the past 9 years and has trained more than 600 teachers to use Forgiveness Education. The Program is now being taught to more than 6,000 students as part of the Greek Forgiveness Education Program that Dr. Galiti directs.

Ph.D., M.Ed., has been conducting training workshops for Greek teachers for the past 9 years and has trained more than 600 teachers to use Forgiveness Education. The Program is now being taught to more than 6,000 students as part of the Greek Forgiveness Education Program that Dr. Galiti directs.

. - Annette Shannon, Learning Support Teacher at Holy Cross Girls’ School in Belfast, Northern Ireland, has been teaching and coordinating the school’s Forgiveness Education Program for the past 11 years.

Another prominent participant in World Education Week, Bishop Kortu Brown, Chairman/CEO of Church Aid Inc., has been National Coordinator of the Liberia Forgiveness Education Program since it was established by Dr. Enright nearly 10 years ago. Bishop Brown also appears in a 30-second promotional video about the week’s activities.

The widely acclaimed Forgiveness Education Program, developed by Dr. Enright along with collaborating curriculum experts and experienced teachers, is administered by the International Forgiveness Institute. Using children’s story books and Social Emotional Learning (SEL) techniques, the Program teaches students about the five moral qualities most important to forgiving another person–inherent worth, moral love, kindness, respect and generosity. The Program is now being used in more than 30 countries around the world.

Learn more and register for World Education Week activities (all sessions are free) on the Forgiveness Forum website.

Can you give me an example of when forgiving is not a good option?

Yes, and here are two examples. For example 1, the one who might forgive realizes that there really was no injustice. There was, instead, a misunderstanding between two people. Under this condition, forgiving is not a good option. For example 2, the person truly was treated unjustly by another, but this happened very recently. The one considering forgiving is not ready and needs some time to work through the anger. In this case, it may be best to wait, process the anger, and then decide if forgiving is the way to go now. Forgiving is a free will choice and sometimes we need time to process what happened and to examine our inner world before starting to forgive.

The essence of forgiveness is to love those who have not loved us. Yet, I cannot at this point feel love for the one who hurt me. Does this mean that I am not forgiving?

From the Aristotelian philosophical perspective, there is a difference between what forgiveness is at its core (in its Essence) and how we as imperfect people actually practice forgiving (what Aristotle calls the Existence of forgiving). We do not have to reach perfection in our Existence of forgiving. In fact, Aristotle comforts us by saying that is it is very difficult to reach the exact Essence of the moral virtues because we are constantly growing in these virtues as we practice them. So, if you do not feel love for the one who hurt you, this does not mean that you are not forgiving as long as you are motivated to reduce your resentment toward the person and to offer goodness of some kind (such as civility) to the other. As you practice forgiving, over and over, you may grow in the moral virtue of agape love (which is love in the service of the other even when it is difficult and painful to do) toward the person.

Which is harder, to forgive close family members or to forgive strangers?

In my experience, it is much harder, on the average, to forgive close family members. This is the case because those close to us are supposed to love us and not treat us deeply unjustly. There can be a deep sense of betrayal when someone, who is supposed to love us, acts very unjustly. As one more point, the answer to your question also depends on how serious the injustice is from the family member and from the stranger. If the stranger’s injustice is horrific, then this person will be harder to forgive than family members who do not act nearly as unjustly.

What has been your experience of seeing people forgive because they feel they have to (because of pressure from others or because of religious beliefs) and those who willingly choose to forgive on their own?

The idea of forgiving “because they feel they have to” do this is somewhat complex. For example, there is nothing wrong with others pointing a person in the direction of forgiveness. This can be of great help, especially if the person misunderstands what forgiveness is or has hardly tried it before. On the other hand, hovering over a person and not letting that person see the beauty of forgiving, and choosing it as part of one’s own free will, can be coercion. This is not helpful because the person is not necessarily being drawn to the beauty of forgiveness. So, if we make the distinction between educating a person and assisting the person to deeply understand forgiveness on the one hand and forcing on the other, we can see that the former is good and the latter is not. We need a gentle approach when helping others to think about forgiveness.