Tagged: “Why Forgive?”

The third of 15 criticisms I have seen about forgiveness: Forgiveness is a herd mentality. People only forgive because everyone else is forgiving. It is a way to conform, to fit in with the crowd.

While others’ forgiving can be a positive encouragement for you, your forgiving still is your own free will decision, as in your point 1 which we addressed.

Expert Forgiveness Advice from Media Giants

The 6th-largest newspaper in the US and the country’s most popular weekly supermarket magazine have highlighted the importance of forgiveness in the past few days. The Washington Post and Woman’s World recently ran articles offering advice on how to forgive from forgiveness experts including Dr. Robert Enright, co-founder of the International Forgiveness Institute.

“Moving lessons on forgiveness out of religious spaces and into schools”

This full-length article is featured in the Jan. 27 issue of The Washington Post (a 146-year-old daily newspaper with average weekday circulation of nearly half a million). The article highlights the benefits of forgiveness education work being done by Dr. Enright, one of his research associates Dr. Suzanne Freedman (University of Northern Iowa), and Dr. Frederic Luskin (director of the Stanford University Forgiveness Project).

highlights the benefits of forgiveness education work being done by Dr. Enright, one of his research associates Dr. Suzanne Freedman (University of Northern Iowa), and Dr. Frederic Luskin (director of the Stanford University Forgiveness Project).

“. . .people who forgive are less anxious and angry and have lower blood pressure, improved cholesterol levels and a better quality of sleep,” the article states, citing the published literature. “Studies also show that children who learn how to forgive are better adjusted socially and have higher levels of self-esteem than those who don’t. They even perform better academically.”

Much of the article focuses on Dr. Enright’s forgiveness education work in Northern Ireland, where both public and private schools have been teaching his forgiveness curriculum for the past 21 years. One school, Mount St. Michael’s Primary School, a Catholic school in Randalstown, 23 miles from Belfast, recently paired up with a Protestant school in the same town to offer forgiveness education to a joint class of 7-to-9-year-olds.

“We really need this over here,” St. Michael’s Principal Philip Lavery said. “We teach children how to read and write, but we have to spend more time teaching them how to live, how to be members of a society.”

At Stranmillis University College in Belfast, forgiveness education is a required subject for all students in its teacher training program, where they learn the protocol developed by Dr. Enright and his team at the University of Wisconsin. In a country that has been torn for decades by religious violence, the article concludes, it is only through forgiveness and unselfish love that “we can leave the past behind us.”

Read the full article in The Washington Post.

“Expert Advice: How Can I Stop Beating Myself Up?”

This article appears in the January 26 issue of Woman’s World magazine (circulation 1.6 million). Subtitled “Sometimes it’s harder to forgive yourself than to forgive others,” the article presents “easy ways to silence the self-blame and welcome self-love.”

The article is based on interviews with three mental health specialists the publication calls its Expert Panel:

- Robert Enright, Ph.D., educational psychologist and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison;

- Everett Worthington, Ph.D., Commonwealth Professor Emeritus at Virginia Commonwealth University; and,

- Kathryn J. Norlock, Ph.D., author of The Moral Psychology of Forgiveness and an ethics professor at Trent University in Ontario, Canada.

The first (and, arguably, the most important) bit of advice offered in the Woman’s World article is:

Remember You’re Worthy – The very first step to self-forgiveness is simply knowing you deserve it, says expert Robert Enright, PhD. “This doesn’t mean letting yourself off the hook without reflecting on what’s happened; rather, it’s reminding yourself that you’re worthy when you’ve started believing the lie that you’re not.” Just reminding yourself that you deserve this nurturing will begin to transform guilt into self-compassion.

Read the full article in Woman’s World.

What does love have to do with it? Do you really think that to forgive, we have to love the one who was brutal to us?

Does Forgiveness Work? Let’s Ask the Experts. . .

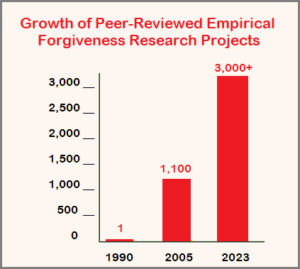

The benefits of forgiveness have been discussed and debated for centuries but scientific evidence that forgiveness actually “works” has been scant. All that has changed during the past few decades as legions of psychologists and clinicians have begun studying the ancient virtue from a stringently documented, peer-reviewed empirical perspective.

Dr. Robert Enright, an educational psychologist labeled the “forgiveness trailblazer” by Time magazine (and co-founder of the International Forgiveness Institute), published the first scientific study on person-to-person forgiveness in 1989. In the 15 years following the publication of that article in the Journal of Adolescence, the number of published forgiveness articles had jumped to more than 1,100. And today, researchers can pore through more than 3,000 published articles brandishing empirical evidence on the virtue of forgiveness.

Dr. Robert Enright, an educational psychologist labeled the “forgiveness trailblazer” by Time magazine (and co-founder of the International Forgiveness Institute), published the first scientific study on person-to-person forgiveness in 1989. In the 15 years following the publication of that article in the Journal of Adolescence, the number of published forgiveness articles had jumped to more than 1,100. And today, researchers can pore through more than 3,000 published articles brandishing empirical evidence on the virtue of forgiveness.

Here is a quick look at several recent research reports related to the benefits of forgiveness:

Forgiveness Reduces Suicidal Behavior

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young adults and about 1,100 college students die by suicide each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). According to a study of 158 college students, all suffering from mild to severe depression, psychologists at East Tennessee State University found that:

“Students who are more capable of forgiving themselves and others after stressful life events or interpersonal problems have lower rates of suicidal behavior than their peers who are less able to forgive. This study points out that interventions that boost levels of forgiveness can increase self-esteem, hopefulness, positive emotions toward other people, and perceived self-control while reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and drug use.”

Source: Forgiveness, Depression, and Suicidal Behavior Among a Diverse Sample of College Students.

![]()

Forgiveness Education Program Reduces Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

After implementation of Dr. Enright’s Forgiveness Education curriculum for high school students in Turkey, study results demonstrated that:

“Forgiveness Education has led to significant decrease in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Conclusion: Forgiveness Education can be used effectively for adolescents in school settings.”

![]()

Even Brief Enright Forgiveness Education Programs Improve Health

Chinese college students demonstrated positive improvement in emotional health following brief (4 sessions compared to the normal 12 sessions) exposure to Enright Forgiveness Education curriculum classes. According to the study:

“The analysis of the pretest and post-test scores indicated that both the Enright Psycho-social Programme and the Chinese Value-oriented Programme had positive effects on improving participants’ general emotional forgiveness, decreasing their negative emotions toward the offender, and improving life satisfaction.”

![]()

Forgiveness Significantly Predicts Life Satisfaction

Researchers have begun to investigate the relationship between happiness and subjective factors like Forgiveness. A study with 380 students from different departments of Bursa Uludag University in Bursa, Turkey, found that:

“Happiness has been found to be negatively related to stress and positively related to positive emotions, satisfying relationships, self-esteem, forgiveness, self-compassion, and quality of friendships.Results in this study also indicate that forgiveness and life satisfaction are positively related and that forgiveness significantly predicts life satisfaction. For this reason, my results are important for psychological healthcare workers, who can include these variables into their supportive and preventive programs in order to assess important characteristics that contribute to good psychological health.”

Source: Predictive effects of subjective happiness, forgiveness, and rumination on life satisfaction.

![]()

I prefer anger to forgiveness. It empowers me. What do you think?

Anger at first when you are treated unjustly is reasonable because you are seeing that you are a person who deserves respect. Yet, where do you draw the line? When is this early anger sufficient? Do you want to keep the anger for a month? A year? How about 30 years? Also, what about the intensity of the anger. Do you want to be fuming inside for those 30 years? Do you think you will feel empowered if you live this way or could it wear you down?