Famous People

A Forgotten History of Polish People’s Forgiveness After Auschwitz

This is a guest blog post from Edward Reid, who runs the “Polish History” site on Facebook. The essay, copied in full here with Mr. Reid’s permission, shows the forgiving nature of the Polish people after Rudolf Höss brutalized so many in Auschwitz.

Facebook page – April 16, 2025

The essay is as follows:

Image by Karolina Grabowska, Pexels.com

In 1947, Rudolf Höss, commandant of German KL Auschwitz in the years 1940-1943, was sentenced to death by the Supreme National Tribunal in Poland. Two weeks later, on 16 April, he was hanged next to the crematorium of the former concentration camp.

Rudolf Höss did not fear death. What he feared was torture, which he believed was inevitable at the hands of his Polish captors. After all, Auschwitz had been located in German-occupied Poland, and it was the Polish people who had suffered so terribly under his command.

What he encountered instead left him stunned.

He was not met with hatred or violence, but with decency and restraint. “I have to confess that I never would have expected to be treated so decently and so kindly in a Polish prison,” he later wrote. That unexpected mercy opened something within him. Several of the Polish guards, themselves former prisoners of Auschwitz, quietly showed him the tattoos burned into their arms. Rather than seek revenge, they treated him with dignity.

It was an act that brought him shame. If those he had helped torment could offer him humanity, then perhaps, he began to wonder, God might offer him mercy as well. Apathy gave way to guilt. Recognition replaced denial. He began to grasp the weight of what he had done.

For the first time, his soul responded to a flicker of love. The ideology he had once followed so blindly had taught him that Poles were inferior, little more than cattle. But now, through their compassion, he saw clearly the humanity of those he had dehumanized. And in that realization, he began to understand the true gravity of his crimes.“In the solitude of my prison cell, I have come to the bitter recognition that I have sinned gravely against humanity,” he wrote. “I caused unspeakable suffering for the Polish people in particular. I am to pay for this with my life. May the Lord God forgive one day what I have done. I ask the Polish people for forgiveness.”

By all accounts, his repentance appeared genuine. On April 4, 1947, which was Good Friday that year, Höss asked to make a confession. The prison guards struggled to find a priest who spoke fluent German. That is when Höss remembered Father Władysław Lohn, a Jesuit he had once saved from execution. The guards located him in Łagiewniki, Poland, where he was then serving as chaplain at the Shrine of Divine Mercy. Father Lohn heard his confession on the Thursday of Easter week. The next day, he gave him Holy Communion and Viaticum.

Witnesses said that as Höss knelt in his prison cell, he appeared like a small boy.

The man who had once been trained to suppress all weakness now wept openly.

Five days later, on April 16, 1947, as the noose was placed around his neck at Auschwitz, Father Tadeusz Zaremba stood beside him and recited the prayers for the dying.

Whether or not he deserved forgiveness is something each person must decide for themselves. But the crimes committed against the Polish people must never be forgotten.

And neither should the quiet strength of those who, even in the face of unimaginable suffering, chose mercy. This is also why the Polish people, despite their profound heroism and the scale of their suffering were left behind in the telling of history. They did not turn their pain into politics or profit. They did not build monuments to themselves and demand all the world bow to their wounds. They endured in silence behind the Iron Curtain. Many showed mercy when they had every right to hate. And in doing so, they were forgotten by a world that rewards those who shout the loudest, not those who suffer with dignity.

But the truth remains. It was not only the victims who showed humanity – it was the forgotten Polish guards, the priests, the villagers, the mothers, the resistance fighters. They gave the world a quiet, sacred kind of courage.

The kind that history has yet to fully honor…

Power Versus Love

Current political norms seem to have power as a way to achieve objectives. In light of this, perhaps it is time to revisit the contrast between power and love. The following is an excerpt from the book, 8 Keys to Forgiveness (R. Enright, 2015).

Here are 10 pairs of contrasting statements differentiating between power and love, which may be useful in helping you forgive:

Power says, “Me first.”

Love asks, “How may I serve you today?”

Power manipulates.

Love builds up.

Power exhausts others.

Love refreshes them.

Power is rarely happy in any true sense.

Love understands happiness.

Power is highly rewarded in cultures that worship money.

Love considers money to be a means to an end, not an end itself.

Power steps on others.

Love is a bridge to others’ betterment.

Power wounds—even the one who exerts the power.

Love binds up the wounds, even in the self.

Power is joyless even when it is in control.

Love includes joy.

Power does not understand love.

Love does understand power and is not impressed.

Power see forgiveness as weakness and so resentments might remain.

Love sees forgiveness as a strength and so works to eliminate resentment.

Power rarely lasts because it eventually turns inward, exhausting itself. Look at slavery in the United States, or the supposedly all-powerful “Thousand-Year Reich” of the Nazis, or even the presence of the Berlin Wall, intended to imprison thought, freedom, and persons . . . forever. Love endures even in the face of grave power against it.

![]()

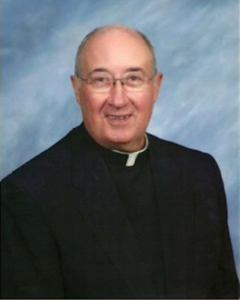

In Memoriam: A Tribute to Our Long-Time Board Member and Friend, Msgr. John Hebl

On March 11, 2024, our International Forgiveness Institute (IFI) lost our Board Member and friend, Msgr. John Hebl, who passed away at his home in Oxford, Wisconsin. He joined our IFI in 1994 and gave us 30 years of wonderful service with his wisdom and passion for forgiveness. He is an important figure in forgiveness science because he was the very first person, in the entire history of psychology, who did an empirically-based, peer-reviewed published study on a forgiveness intervention. In that article, published by the American Psychological Association’s journal, Psychotherapy, he screened 24 elderly women  who suffered injustices, mostly within the family and friendship contexts. He randomized the women into the experimental group, in which he brought them through our Process Model of Forgiveness, and the control group, in which social issues were discussed, such as the influence of senior citizens on society, attitudes toward aging, and family conflicts. Each lasted for eight sessions, once a week, for about an hour each time. Findings showed that the participants in the experimental group grew statistically significantly more than the control group participants in forgiving people who have hurt them. Those in the experimental group also grew statistically significantly more than the control group in their willingness to forgive others in general. The reference to this historical work is this:

who suffered injustices, mostly within the family and friendship contexts. He randomized the women into the experimental group, in which he brought them through our Process Model of Forgiveness, and the control group, in which social issues were discussed, such as the influence of senior citizens on society, attitudes toward aging, and family conflicts. Each lasted for eight sessions, once a week, for about an hour each time. Findings showed that the participants in the experimental group grew statistically significantly more than the control group participants in forgiving people who have hurt them. Those in the experimental group also grew statistically significantly more than the control group in their willingness to forgive others in general. The reference to this historical work is this:

Hebl, J., & Enright, R. D. (1993). Forgiveness as a psychotherapeutic goal with elderly females. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 30(4), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.30.4.658

Msgr. John was a dynamic, busy person as he led a Catholic parish and, at the same time, pursued successfully a doctoral degree in counseling psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he did the groundbreaking research described above. Prior to this, he was a Brigadier General in the United States military service. I used to kid him, saying, “We all will have to address you as Father, Doctor, General Hebl!”

Rest in peace, Msgr. Hebl. Thank you for being a pioneer in forgiveness research, for serving people all these many years, and for contributing to a better world.

![]()

An Example of Finding Meaning in Deep Suffering: In Honor of Eva Mozes Kor

Consider one person’s meaning in a dramatic case of grave suffering. Eva Mozes Kor was one of the Jewish twins on whom Josef Mengele did his evil experiments in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II. In the film Forgiving Dr. Mengele, Mrs. Kor tells her story of survival and ultimate forgiveness of this notorious doctor, also known as the “Angel of Death.”

In describing her imprisonment as a child at Auschwitz, she said, “It is a place that I lived between life and death.” Soon after her imprisonment in the concentration camp, young Eva was injected with a lethal drug, so powerful that Mengele pronounced, after examining her, that she had only 2 weeks to live. “I refused to die,” was her response.

Her meaning in what she was suffering in the immediate short run was to prove Mengele wrong and thus to do anything that she possibly could to survive. Her second meaning in her suffering was to survive for the sake of her twin sister, Miriam. She knew that if she, Eva, died, Mengele immediately would kill Miriam with an injection to the heart and then do a comparative autopsy on the two sisters. “I spoiled the experiment,” was her understated conclusion. A third meaning in her suffering, a longer but still short-term goal, was to endure it so that she could be reunited with Miriam. A long-term goal from her suffering ultimately was to forgive this man who had no concern whatsoever for her life or the lives of those he condemned to the gas chamber. She willed her own survival against great odds, and she made it.

In this case, fiendish power met a fierce will to survive. Upon forgiving Mengele, she saw great meaning in what she had suffered. She has addressed many student groups, showing them a better way than carrying resentment through life. She opened a holocaust museum in a small town in the United States. And she realizes that her suffering and subsequent forgiveness both have a meaning in challenging others to consider forgiving people for whatever injustices they are enduring.

Her ultimate message is that forgiveness is stronger than Nazi power. And it has helped her to thrive.

Robert

» Excerpt from Chapter 5 of the book, 8 Keys to Forgiveness, R. Enright. Norton publishers.

Read more about Eva Mozes Kor and her forgiveness work with Dr. Robert Enright:

- Let’s Heal the World Through Forgiveness

- Nothing Good Ever Comes from Anger

- In Memoriam: Eva Mozes Kor

In Memoriam – Archbishop Desmond M. Tutu

Editor’s Note: Archbishop Desmond M. Tutu, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Anglican cleric who helped end apartheid in his native South Africa, died Sunday at the age of 90. Called the “Man of Forgiveness” by The New York Times, Archbishop Tutu worked closely for many years with Roy Lloyd, President of the International Forgiveness Institute’s Board of Directors. Here are Dr. Lloyd’s reflections on his years with the incomparable Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was a person of immense generosity, joy and courage and I was privileged to call him a friend. Desmond and I knew each other, over many years, through anti-apartheid work including sanctions against South Africa, divestment efforts and protests. I also was privileged to spend a considerable amount of time with him when he was in New York City at General Theological Seminary as a scholar in residence. Later on, when he was speaking and teaching at Emory University in Atlanta, he and I produced TV and radio spots enlisting aid for those suffering so horrifically in the Kosovo conflict. This was entirely in character. For him, caring meant acting, not just talking about it.

This was a man who stood on principle, calling out oppression of every kind, albeit with a generosity of spirit, decency and respect. Desmond believed that when people can come face-to-face with each other to speak the truth with sincerity, then it is possible to achieve closure and a more equitable outcome.

That was certainly at the heart of his leadership of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa that brought together perpetrators of violence facing people who had been persecuted. An open atmosphere was created in which participants could confess what they had done or be candid about what they had endured. The desired result of mutual responsibility for moving forward in a more positive way was achieved by facing reality, while not denying justice. Those responsible for their actions received whatever penalty was necessary. Yet, that wasn’t the end of the story. Those who were sincere in their confession were forgiven and welcomed into a higher level of meaning in interracial relationships.

It was through a commitment to these kinds of meaningful endeavors that Desmond and I became involved in the initial days of the International Forgiveness Institute. Desmond declared, at our first national conference, the message that drove his lifelong ministry: “Without forgiveness there is no future.”

This is the central message of the International Forgiveness Institute (IFI).

Forgiveness is an opportunity to accept that gift for ourselves, liberating us from whatever harm we have experienced and the freedom to offer it to others. Desmond knew well that this doesn’t necessarily lead to reconciliation or to the denial of justice. Those who commit harm deserve a just penalty. However, through forgiveness the equation is vastly changed. A never-ending problem of harm that challenges us can become an opportunity for growth, renewal and regeneration of life.

The Archbishop was someone who was effervescent in personality, continually joyous and always with a twinkle in his eye. This was a hero who was continually committed to walking the hard road to achieve the common good. I always found him to be looking forward rather than backward. As the saying goes, he always had his eye on the prize.

“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

I firmly believe that Desmond Tutu provided a template for how all of us can lead a meaningful existence—one that celebrates the bonds of our humanity and grants to each we meet our thoughtfulness, consideration and esteem.

We at the International Forgiveness Institute pay homage to this marvelous man and are honored by his years of commitment to forgiveness and as an honorary IFI board member.

Roy Lloyd

President, Board of Directors

International Forgiveness Institute

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Endnotes:

- Before his death, Archbishop Tutu had served as an Honorary Member of the International Forgiveness Institute Board of Directors for more than 25 years.

- In 1995, Archbishop Tutu provided the opening remarks (by recorded audio) at the historic international forgiveness conference hosted by the IFI and held at the University of Wisconsin-Madison–the first academic forgiveness conference ever held at any university in the world.

- Archbishop Tutu wrote the “Foreword” to the 1998 book Exploring Forgiveness, a collection of forgiveness essays edited by IFI-founder Dr. Robert Enright and philosopher Joanna North. That Foreword is titled “Without Forgiveness There Is No Future.”

- In 2014, Dr. Enright announced to IFI website followers the Tutu Global Forgiveness Challenge–a free 30-day program developed by Archbishop Tutu and his daughter Mpho Tutu, designed to teach the world how to forgive. In that article, Dr. Enright said of Archbishop Tutu: “He has lived forgiveness. He has embodied it.”

- Read “Quotations on Forgiveness from Desmond Tutu.”

- Read “Desmond Tutu Wins 2013 Templeton Prize for Forgiveness Work.”

- Called the “Man of Forgiveness” by The New York Times, Archbishop Tutu is the author of several books including: No Future without Forgiveness and The Book of Forgiving: The Fourfold Path for Healing Ourselves and Our World.

- Read a biographical account of Archbishop Tutu’s life and global activities in The New York Times or watch a biographical video at CNN News. Archbishop Tutu is survived by his wife of 66 years, Leah, and their four children.

_____________________________________________________________

About Roy Lloyd:

In addition to being the long-term President of the IFI Board of Directors, Roy Lloyd is an IFI founding director and contributing writer. He is a retired communications executive with graduate degrees in education, communications and theology. Before retiring to Springfield, MO, Dr. Lloyd was a regular commentator on all-news radio station 1010 WINS in New York City and he appeared with Desmond Tutu on Good Morning America, CNN, Religion and Ethics Newsweekly, Live with Regis and Kelly, and other programs. His high-profile career activities included his service as media officer for the Jesse Jackson trip to Belgrade in 1999 that gained the release of three American soldiers held by the Milošević regime. He has also served as executive producer of numerous network television programs and as producer and host of Public Television’s “Perspectives” series. He can be contacted at: roytlloyd@gmail.com