Tagged: “New Ideas”

Forgiveness Can Expand Your Vision

When we are consistently angry over deep injustices against us, it can narrow our vision. We think about the person and what happened, we dream about the person, we can become preoccupied with the past.

Image by Pexels.com

In contrast, when we forgive, we see both a more complete person in the one who acted badly and an expanded hope for the future. As we forgive one person, we often are motivated to forgive others. As we continue to forgive, there often develops in us a motivation to assist others in their suffering. Our vision expands so that we see beneath the surface of others. We see their pain……and we want to help. As we continue to forgive and to aid others in their suffering, we can begin to expand our view of humanity, of who each person is as someone of inherent worth, special, unique, and irreplaceable.

As we forgive, we expand our vision of: a) the one who hurt us; b) hurting people in general; c) and humanity in general. The expansion tends to be what Lewis Smedes used to call “seeing with new eyes.” These are eyes of expansion, toward greater positivity and hope for humanity. These are eyes of expansion in seeing the self in new ways, with a new meaning and purpose in life for others.

Forgiveness is part of love and beauty and so as we forgive, we become more attuned to both love and beauty and want to contribute more of these into the world. The expanded vision does not lessen what happened, but it makes what happened more bearable as healing takes place and love expands.

![]()

What Are the Implications for Forgiveness if We Take the Materialist Perspective that Free Will Does Not Exist?

Nine years ago, I was asked this same question. It is starting to arise again as people consider the materialist philosophy that circumstances and issues other than free will choices determine how people behave. I introduce my answer from 2014 here and add to it. The conclusion remains: Free will is necessary if we are to understand right and wrong and even if we are to understand forgiveness.

(Image by Pexels.com)

We are all connected and so one person’s actions are not necessarily independent from others’ actions. Is this true? Some Eastern philosophies say this. Some Western psychologies say this, too. For example, family systems theory surmises that a misbehaving child likely is being influenced by pressures within the family generated by others’ behavior both inside and outside that family. Psychodynamic theories in psychology say that an adult’s actions can have causes going back to how this person was treated as a child.

Given all of the interrelated ideas above about our being interrelated in our actions, we can then make at least two moves in explaining people’s behavior: 1) no one can truly help certain actions because of others’ influences over us or 2) we all have free will and choose to act rightly or wrongly even if others’ make it hard to be good.

If we take the first turn on our journey of understanding persons, then we weaken such ideas as “right and wrong,” “justice,” and “forgiveness.” After all, how can we say that one person acted wrongly? if we are all so interconnected, then this person is not acting with any kind of genuine volition. In a certain way, his misbehavior can implicate his father, who can implicate his mother, who can implicate……..On it goes until we all share the blame which weakens the case against the original person and his actions under consideration.

If we take the second turn on our journey of understanding persons, then we strengthen such ideas as “right and wrong,” “justice,” and “forgiveness.” After all, the person, even though pressed in on all sides by others, has choices. One need not, for example, hit another person because of frustration. One’s mother has not so abused this person that she was left with one and only one option. Yes, the mother’s misbehavior (whatever it was) may make it difficult for the daughter to control her temper, but control it to a degree she can.

Free will. Independent choices. Break the laws of morality (you will not take the life of an innocent person, for example), and you do wrong. If the wrong is done to me, I can forgive. If the other does not have free will, then an apparent wrong is just that—-apparent. Do I then forgive a person for a wrong? The conclusion is no longer clear. We will have to redefine forgiveness in this case to retain the use of the word “forgiveness.” Forgiveness becomes a kind of acceptance of all along with their actions, no matter how wrong they might appear to be. We still retain such words as “compassion” and “understanding,” but the word forgiveness itself begins to fade.

If the world ever loses the word forgiveness and its true meaning, we are in very big trouble. Inner unrest and conflict within families and communities may know no end. To retain this vital concept, we must retain the truth of free will for each person.

![]()

Does Forgiveness Work? Let’s Ask the Experts. . .

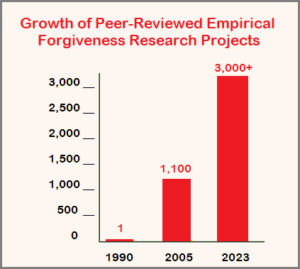

The benefits of forgiveness have been discussed and debated for centuries but scientific evidence that forgiveness actually “works” has been scant. All that has changed during the past few decades as legions of psychologists and clinicians have begun studying the ancient virtue from a stringently documented, peer-reviewed empirical perspective.

Dr. Robert Enright, an educational psychologist labeled the “forgiveness trailblazer” by Time magazine (and co-founder of the International Forgiveness Institute), published the first scientific study on person-to-person forgiveness in 1989. In the 15 years following the publication of that article in the Journal of Adolescence, the number of published forgiveness articles had jumped to more than 1,100. And today, researchers can pore through more than 3,000 published articles brandishing empirical evidence on the virtue of forgiveness.

Dr. Robert Enright, an educational psychologist labeled the “forgiveness trailblazer” by Time magazine (and co-founder of the International Forgiveness Institute), published the first scientific study on person-to-person forgiveness in 1989. In the 15 years following the publication of that article in the Journal of Adolescence, the number of published forgiveness articles had jumped to more than 1,100. And today, researchers can pore through more than 3,000 published articles brandishing empirical evidence on the virtue of forgiveness.

Here is a quick look at several recent research reports related to the benefits of forgiveness:

Forgiveness Reduces Suicidal Behavior

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young adults and about 1,100 college students die by suicide each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). According to a study of 158 college students, all suffering from mild to severe depression, psychologists at East Tennessee State University found that:

“Students who are more capable of forgiving themselves and others after stressful life events or interpersonal problems have lower rates of suicidal behavior than their peers who are less able to forgive. This study points out that interventions that boost levels of forgiveness can increase self-esteem, hopefulness, positive emotions toward other people, and perceived self-control while reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and drug use.”

Source: Forgiveness, Depression, and Suicidal Behavior Among a Diverse Sample of College Students.

![]()

Forgiveness Education Program Reduces Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

After implementation of Dr. Enright’s Forgiveness Education curriculum for high school students in Turkey, study results demonstrated that:

“Forgiveness Education has led to significant decrease in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Conclusion: Forgiveness Education can be used effectively for adolescents in school settings.”

![]()

Even Brief Enright Forgiveness Education Programs Improve Health

Chinese college students demonstrated positive improvement in emotional health following brief (4 sessions compared to the normal 12 sessions) exposure to Enright Forgiveness Education curriculum classes. According to the study:

“The analysis of the pretest and post-test scores indicated that both the Enright Psycho-social Programme and the Chinese Value-oriented Programme had positive effects on improving participants’ general emotional forgiveness, decreasing their negative emotions toward the offender, and improving life satisfaction.”

![]()

Forgiveness Significantly Predicts Life Satisfaction

Researchers have begun to investigate the relationship between happiness and subjective factors like Forgiveness. A study with 380 students from different departments of Bursa Uludag University in Bursa, Turkey, found that:

“Happiness has been found to be negatively related to stress and positively related to positive emotions, satisfying relationships, self-esteem, forgiveness, self-compassion, and quality of friendships.Results in this study also indicate that forgiveness and life satisfaction are positively related and that forgiveness significantly predicts life satisfaction. For this reason, my results are important for psychological healthcare workers, who can include these variables into their supportive and preventive programs in order to assess important characteristics that contribute to good psychological health.”

Source: Predictive effects of subjective happiness, forgiveness, and rumination on life satisfaction.

![]()

A Reflection on the International Educational Conference on Agape Love and Forgiveness, Madison, Wisconsin, July 19-20, 2022

Main Point 1: Despite cross-cultural differences, forgiveness has a common meaning across historical time and across cultures.

Main Point 2: To my knowledge, there never has been a conference on agape and forgiveness before this one.

Main Point 3: It is time for modern culture to reawaken the ancient moral virtues of agape and forgiveness for the good of individuals, families, and communities.

After over a year of detailed preparation by Jacqueline Song and the dedicated team, the agape love and forgiveness conference is now history. That history is preserved in the videos which have captured each talk presented at the conference (the videos are available here: Agape Love and Forgiveness Conference Videos).

I have at least three take-away points as I reflect on this conference:

- The cultural diversity was strong, with presentations by people from Israel, Northern Ireland, the Philippines, Taiwan, and the United States. Despite the wide cultural differences, one thing

was clear: The meaning of both agape and forgiveness do not change as we get on an airplane and visit cultures that are far away from one another. Instead, the core meaning of agape remains in that as a person loves in this way, it is for the other person(s) and the expression of this love can be challenging for the one who willingly offers it. The core meaning of forgiveness remains as a person, unjustly treated by others, a) makes the free will decision to be good to those who acted unfairly, b) sees the inherent worth in those others, c) feels some compassion for them, d) willingly bears the pain on those others’ behalf, and e) offers goodness of some kind toward them. Yes, those who forgive may not reach all five of these characteristics, but they remain the goal, that to which we want to strive if excellence in forgiveness is our end point. Yes, there are important cultural nuances as one Islamic educator introduced forgiveness to the students with quotations from the Qu’ran and as an educator from a Christian school opened the New Testament to the students. The rich diversity had a glue that bound all together—-the objective reality of what these two moral virtues mean across historical time and across cultures. Objective meaning met cultural nuance at the conference.

was clear: The meaning of both agape and forgiveness do not change as we get on an airplane and visit cultures that are far away from one another. Instead, the core meaning of agape remains in that as a person loves in this way, it is for the other person(s) and the expression of this love can be challenging for the one who willingly offers it. The core meaning of forgiveness remains as a person, unjustly treated by others, a) makes the free will decision to be good to those who acted unfairly, b) sees the inherent worth in those others, c) feels some compassion for them, d) willingly bears the pain on those others’ behalf, and e) offers goodness of some kind toward them. Yes, those who forgive may not reach all five of these characteristics, but they remain the goal, that to which we want to strive if excellence in forgiveness is our end point. Yes, there are important cultural nuances as one Islamic educator introduced forgiveness to the students with quotations from the Qu’ran and as an educator from a Christian school opened the New Testament to the students. The rich diversity had a glue that bound all together—-the objective reality of what these two moral virtues mean across historical time and across cultures. Objective meaning met cultural nuance at the conference.

- Unless I missed something in my travels with forgiveness over the past 37 years, I do not think there ever was an international conference that focused specifically on the moral virtues of agape and forgiveness. If this is true, why is it the case? What has happened within humanity so that these two key moral virtues, so prominent for example in Medieval times, would be characteristically ignored in educational contexts with children and academic contexts in university settings? I think the transition from accepting objective truth about moral virtues (for example, justice is what it is no matter where we are in the world even when there are cultural nuances) has given way to an assumption that relativism is the new truth and so we all can choose the virtues we like and define them as we wish. Do you see the contradiction in such a statement? In the abandonment of objective reality that there is a truth, the new thinking is that relativism (in which there is no truth) is the new objective truth. It is time to reintroduce communities to the moral virtues, which we all share as part of our humanity. We need to know what these virtues are by definition and how we can give them away to others for their good, for our good, and for the good of communities.

- When I look across the globe at communities that have experienced conflict, that now carry the weight of the effects of decades and even centuries of conflict, I have come to the conclusion that a reawakening of the moral virtues of agape and forgiveness is vital if we are to heal from the effects of war and continued conflict with all of its mistrust and stereotyping of the human condition. Agape and forgiveness challenge us to see the personhood in everyone with whom we interact, even those who are cruel to us. This does not mean that we cave in to injustices because the moral virtue of justice requires fairness from all. The healing of hearts, families, communities, and nations will be better accomplished if people now can shake off the dust from agape and forgiveness, that have been so ignored in modernism, and find a new way with the old virtues. It seems to me that agape and forgiveness, as a team, is a powerful combination for the healing of trauma for individuals and relationships. I fear a continuation of the same old conflicts in hearts and in interactions if we do not go back and rediscover the life-giving virtues of agape love and forgiveness and bring them forward now in schools, families, houses of worship, and workplaces.

Robert

Ukrainian Research Project Verifies Benefits of Forgiveness in Military Conflict Zones

A just-published scientific study has documented significant mental health benefits derived by Ukrainian citizens who practice forgiveness compared to those who are less willing to forgive. Those findings, according to the authors, will be especially useful for providing appropriate psychological assistance for those adversely affected by the ongoing war with Russia.

Although the Russian invasion of Ukraine began on Feb. 24 of this year, the war in eastern Ukraine has been ongoing since 2014 when a political coup overthrew the pro-Russian government. Since then, more than 14,000 people have been killed in the eastern Ukraine region of Donbas in warfare between ethnic Russians and the Ukrainian military.

That fighting has caused an obvious deterioration of socio-economic living conditions for all Ukrainians. As the armed conflict has intensified, so has the occurrence and severity of mental health issues including depression, psychosomatic diseases, anger and stress-related illnesses, trauma, alienation from friends and relatives, aggressive and antisocial behavior, and criminal activities.

What role the concept of forgiveness can play in a military conflict zone is poorly understood and has never been systematically investigated—until now. A new research report, Forgiveness as a Predictor of Mental Health in Citizens Living in the Military Conflict Zone (2019-2020), was published in the most recent issue of the Journal of Education Culture and Society.

The research was conducted during the years 2019-2020, prior to the Russian invasion. It was authored by Svetlana Kravchuk, a psychologist, and Viacheslav Khalanskyi, a psychotherapist, both of whom practice in Kyiv, the country’s capital city.

Study participants included 302 Ukrainian citizens, half living in the volatile eastern part of the country (where most of the pre-Russian invasion fighting took place), and half living in the more tranquil central part of Ukraine. Using eight different clinically validated scientific tools, the researchers were able to verify the strategic role forgiveness can play in the emotional health of conflict victims.

Here are some of their findings (direct quotes from the report):

- The obtained correlations show that the more a person is prone to forgiveness, the less anxiety and depression a person has.

- A person with a high tendency to forgiveness is characterized by higher levels of decisional forgiveness, hope, emotional forgiveness, tolerance and acceptance of others, mental health, happiness and life satisfaction, as well as tolerance for others’ mistakes.

- The more pronounced degree of tendency to forgiveness is correlated with less pronounced degree of anxiety and depression.

- Hope, happiness, life satisfaction, and tendency to forgiveness can allow citizens living in eastern Ukraine to recover quickly from psychological trauma, contribute to the successful overcoming of negative effects of military conflict and functioning successfully.

According to the authors, the practical value of this research lies in expanding and deepening the understanding of the “phenomenon of forgiveness” and, in the process, developing forgiveness therapy techniques that will work in the mental health sphere throughout Ukraine.

Learn more:

- Read the full report about the role of forgiveness in Ukraine’s military conflict.

- Forgiveness as a Missing Piece to Peace Between Ukraine and Russia (Psychology Today).

- Here’s What You Can Do to Help People in Ukraine Right Now (Time).